Over the past seven years Public World (now trading also as Buurtzorg Britain & Ireland) has introduced scores of organisations and hundreds of nurses and other professionals to the Buurtzorg way of working. We’ve also been a partner in the Transforming Integrated Care in the Community (TICC) project, supported by the EU.

By now we have learnt a lot about the barriers and challenges faced by organisations that are looking to ‘retro-fit’ the Buurtzorg way of putting humanity over bureaucracy, for better outcomes, happier staff and financial sustainability. Now we want to share what we have learnt.

One way we’ll do that is with a series of seven blogs in which our founder, Brendan Martin, will share some of his personal reflections – and, he hopes, offer some provocations. This is the first of the series, and your feedback would be most welcome.

————————————————————————————————————————

In the first of this series, I want to argue that, while I believe as strongly as ever that the principles that underpin the Buurtzorg model should guide the design of future health and care services, even the best services are far from sufficient in themselves.

Since beginning our collaboration with Buurtzorg in 2015, we have worked in around 40 British and Irish settings, and the initial intentions of the organisations that have sought out our help have varied.

What has drawn most of them to Buurtzorg, however, has been its well-deserved reputation for creating and nurturing an organisational environment that enables its nurses and caregivers to do a great job and thrive through self-management.

That is indeed central and indispensable to Buurtzorg’s success, and worth doing for its own sake, which is why we support organisations to learn how to do it. But while self-management expresses Buurtzorg’s purpose, it does not define it.

Buurtzorg’s purpose is to support people to live their lives with meaning and autonomy, based on the belief that we all want to maximise our quality of life and control over it but are also interdependent and in need of warm social interaction.

Providing clinical and personal care are neither Buurtzorg’s purpose nor its only means of achieving it. Just as important – often more so — are the mobilisation and strengthening of a person’s own capabilities and capacities, and those of the social networks around them – friends, family, neighbours, the wider community.

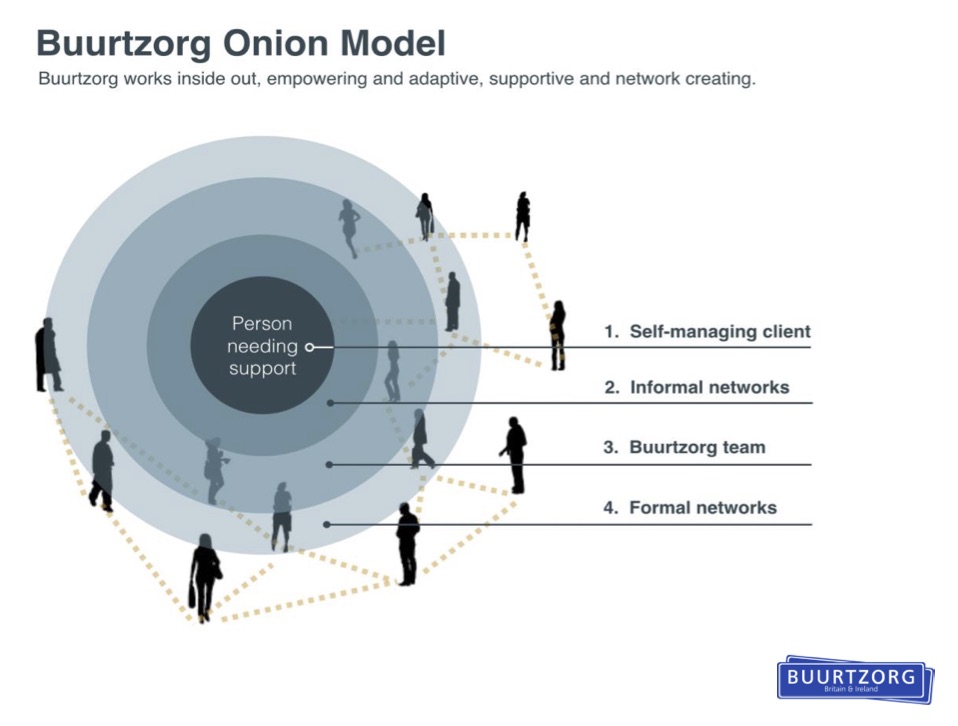

That is why it is important to distinguish the Buurtzorg model – represented graphically in our onion model – from that of some home care companies in Britain that proclaim it as their inspiration for starting up or restructuring.

In claiming to model themselves on Buurtzorg, what some companies unconnected with us mean is that they are delegating more responsibility to their care staff. That can be valuable in itself, if it comes with proper support, as it can improve working lives and enable care to be provided more flexibly and creatively than is possible with ‘time and task’ management.

But I notice also a well-intentioned tendency to offer as a commercial service the kind of human contact and support – keeping people company, for instance —that Buurtzorg teams would try to find, or help generate, in local community networks.

Although transactional relationships and those based on friendship can lead to each other and co-exist, the difference between them matters not only because of wealth inequality but also for reasons of their comparative durability and the nature of social cohesion each generates.

In that regard, it is problematic that ‘social care’ usually refers to a ‘sector’, even an ‘industry’, rather than being a leitmotif of all public policy and economic development. Indeed, its neglect in the latter respect is precisely what inflates demand on the former.

We all need care, so it is never a one-way transaction. At any one time some people need more care than others, which means that those who take on care-giving roles – paid or unpaid — are vulnerable to their own needs being unmet. Meeting everyone’s needs requires a web of community support, to ensure no-one is left isolated and uncared for.

To achieve that, as I have argued before, we need to address the range of economic and social conditions that have rendered our existing social care ‘system’, propped up by a largely undervalued, underpaid and under-supported workforce, unfixable.

To create a society in which we all have the time and energy to care for our loved ones and neighbourhoods, drawing on professional help as necessary, we need more income security and less work-related exhaustion and stress, both of which are well within our grasp if we increase productivity and share its benefits more equitably.

It also demands an end to sex-based inequalities, at work and at home, so that the positive aspects of (often gendered) care-giving, such as love, friendship and real connection, contribute to dismantling rather than further embedding inequity.

Buurtzorg is the Dutch for ‘neighbourhood care’. Mobilising and strengthening community assets is as central to its purpose as meeting the needs of individuals. But returning care work from a largely underpaid, undervalued workforce to unpaid women at home, with even less visibility and support, would be far from progressive.

Our collaboration with Buurtzorg has shown promising glimpses of a future we need to create, and demonstrated some important characteristics of that future.

But to fulfil that potential Buurtzorg’s purpose needs expression not only in the everyday practices of health and care services – which I will explore more in the second blog in this series – but also in political commitment to change the economic and social environment in which those services are provided.

With thanks to Ali Rice, Rose Rickford and Rachel Way for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this piece.